[ 11 ]

Theme and Story Development in Product Design

Using Real Content

Many of us have worked on projects that included no actual content in the wireframes, design, or prototype before the build was pretty much complete and the website or app about to go live. We all know how that story ends and what happens to the carefully designed modules and pages. They break, and it looks horrible. Even worse, if content isn’t carefully considered or covered by the teams involved in building the product, what ends up being included may not be what users or the business actually need.

Throughout my years as a UX designer, I’ve come across clients or internal stakeholders numerous times who insist on putting the actual content into the wireframes and/or the prototype. Usually, however, it’s never really the actual content. It’s draft content, which means it needs to be revised and updated, and then added into the wireframes again. In addition, the way the wireframes are laid out may not be the way the page ends up looking in the final design and build and, as a result, further amendments to the content will most likely be needed.

I’m sure there are teams and projects out for which where this process has worked. In my experience, I find that placing real copy and amending it in wireframes causes more hassle and time wasted than value added. It does, however, raise an important issue: we need to get the content into the pages and views we’re designing and building in order to really see how it works. Content and design do, after all, need to evolve hand in hand.

Far too often we’re designing for only the best-case scenario. Everything lines up neatly. There are no stragglers on a new line, no long words that get cut off in the middle or jump down to the line below, leaving a gap above. No titles that span two or perhaps even three lines, not to mention paragraphs that are simply too long.

Designing with fake content is easy, or at least easier. Designing with and for real content is less so. But that’s what’s going to happen with the wireframes and designs we create: content is going to go in them. And when that happens, it shouldn’t break things. It should fit like a glove, or perhaps more appropriately, what we’ve designed and how we’ve designed it should fit like a glove on the actual content.

I’m all for using Lorem ipsum when used in conjunction with notes about the content that should go in there. Writing real content is hard and takes time. What I might write in my wireframes or prototypes, if I attempt to write real content, will without a doubt be wordier and less to the point than what my fellow copywriter colleagues would write. It’ll also take me substantially longer. That doesn’t mean that I don’t consider the content. I carefully plan out the story that the page and each module should tell, and include an approximation of the amount of copy that should go in, as well as notes on the details that I believe the copy should cover.

Which way you and your product team approach content on your project is up to you. Numerous designers and product people end up writing copy, and there’s no problem with that, as long as it works for the project and as long as the copy is well written. The important thing is that content is considered from the start and that the back-and-forth process of content influencing design, and vice versa, takes place. Everything is connected, and when it comes to good content in product design, everything should be there for a reason, just as in a good story.

The Role of Theme and the Red Thread in Storytelling

When you think about a story and what it is about, whether it’s a book or a film, one of the first things you consider is the plot—what happens in the story and the characters it happens to. If you take it one step further and think about what the story is really about, that’s the theme.

Theme was Aristotle’s third principle behind good storytelling. Lexico defines theme as “an idea that recurs in or pervades a work of art or literature.” Though the theme of a story is often described with words such as love and honor, as is the case with the Hornblower books, in the words of author Robert McKee:

A true theme is not a word, but a sentence—one clear coherent sentence that expresses a story’s irreducible meaning…it implies function: the controlling idea shapes the writer’s strategic choices.1

Theme, in other words, is about what the story means. It’s what the story is about, but through “a different experiential context,” as journalist Larry Brooks puts it,2 and it impacts the story itself.

Most stories have multiple themes. In Harry Potter, for example, the main theme is about good versus evil and the power of love, but there are also themes around friendship and loyalty. You may have a theme that stretches across the whole narrative, and themes that appear in only certain chapters or parts of the story. The strongest stories tend to have themes that interconnect and complement or contrast one another. Although a theme can be obvious, it can also be more nuanced and harder to identify, as is the case in Batman Begins, which features one man’s struggle with his own identify and duality.3

Even if the writer of the story doesn’t explicitly think about its theme, most stories tend to have one. Themes are so closely related to human nature that it’s almost impossible to tell a story without one; the theme can be considered the glue that binds the narrative all together.

When you think about it, in all good stories, things happen for a reason, and in one way or another, everything is connected. Some time ago, my partner D and I watched a horror movie. In one of the scenes, the main character was getting something from a closet. There were two spray cans in the scene, and somehow we just knew that those would play a role later—and sure enough, they did. Walt Disney, as we talked about in Chapter 2, was famous for paying attention to these small details. They are also one of the things my dad really enjoys about being a writer.

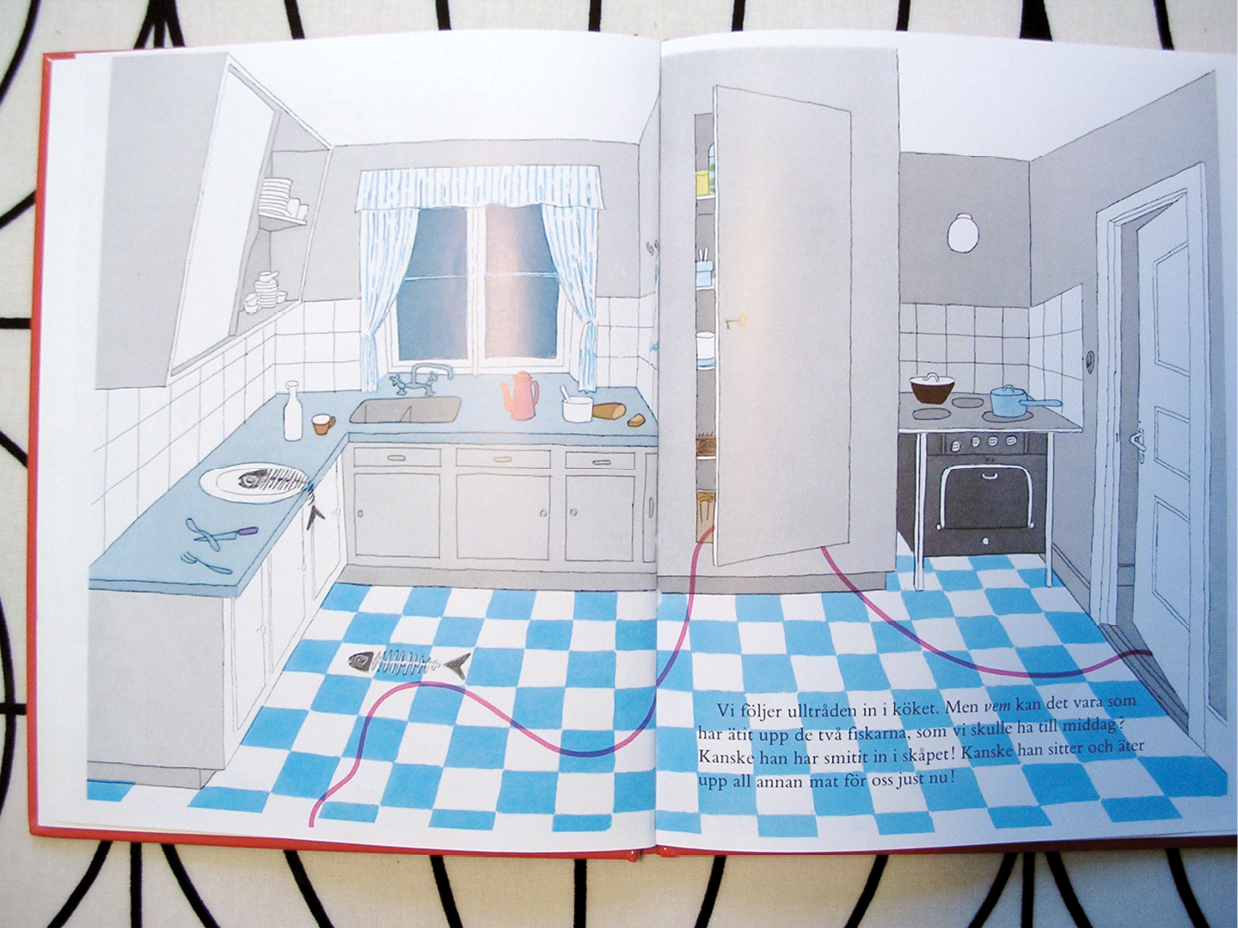

One of the books my parents would read to us when we were kids was the Swedish book Historien om Någon (The History of Somebody) by Åke Löfgren and Egon Möller-Nielsen (Figure 11-1). On the cover of the book is a keyhole with two eyes peering out from inside it, and on the first page of the book, a red piece of string appears. This red string runs through the whole book, guiding the narrative along the events that have taken place, including a fallen vase, and through an open door. As a child, I’d follow that red thread with anticipation of what would be revealed at the end, and I was so pleased when it turned out to be a small kitten.

While the red thread in that childhood story is a very literal one, in Swedish we talk of a red thread, or röd tråd, as the thing that binds the narrative together. Not as a visual line, like the one that you can see in the book, or that you can follow if you go exploring caves, or that you can use to find your way out of a labyrinth as Theseus did in Greek mythology with the help of Ariadne. No, this red thread is an invisible one that runs through it all, a through line. In rhetoric, it’s used as an expression that means that any recitation, particularly longer ones, should have coherence. In storytelling it’s become symbolic for a coherent story, and if it’s not present, or we forget what we were supposed to say when we tell a story or give a talk, we refer having “lost the thread” (“tappat tråden”).

In traditional storytelling, this red thread, or through line, is connected to the plot or theme of the story. It can also be connected to a character and forms the larger and more important aspect of how everything is connected. As producer Barri Evins says:

Using theme as your ‘decider’, from big choices to small ones, is a powerful tool. It empowers you to infuse theme into every aspect of your story, creating a rich and resonant reading experience.4

Figure 11-1

Historien om Någon by Åke Löfgren and Egon Möller-Nielsen

The Role of Theme and the Red Thread in Product Design

In product design, we often have an idea about what we’re working on when we start. This concept hopefully gets further developed and supported by a clearly defined strategy before any UX, design, or development work begins. In the best of scenarios, a red thread runs through it all (Figure 11-2). Perhaps we’ve even started developing experience goals (as covered in Chapter 9) as well as design principles, which help us put words to what the experience should look and feel like. These tools start to connect the pieces of the project.” If the run project is really well run, we’ve also started to work on the content strategy. As the project progresses, this mutually informing relationship between UX, design, content, and development is evolving. If not, we may find ourselves in one of those scenarios where we’re starting, and even completing, the UX, design, and development process before content is properly thought of, and we end up with a website or app that may have looked great on paper but is an absolute disaster when it’s made a reality.

Figure 11-2

The red thread in product design

Having a theme, or many themes, that everyone is absolutely clear on is essential for good product design. Without a theme, essentially anything goes, and the offering and experience can become a car crash. Too often, people resist working through content strategy at the same time that UX design begins—not to mention before UX design begins. This resistance leads to an unclear picture of the content you have to include, and how, as well as why. Just as everything happens for a reason in a good story, everything included in product design should be there for a good reason—because it’s connected, or at least should be. This connection is also what sets great product design and content apart from just good or average product design or content.

With the help of experience goals and design principles, we can ensure that carefully considered and planned-out red threads exist throughout the experiences we design—even if our red thread is not as visible as it was in my childhood book, or the connection isn’t as obvious as it was in that horror movie.

Approaches to Developing Your Story in Traditional Storytelling

There are numerous ways to write a script or a book, from the way you choose to you begin to the bulk of the writing process itself. Some authors and scriptwriters will simply sit down and write. Others use an outline to help structure the narrative and the writing process. The way to go about it will, to some extent, depend on how writing the script or book has come about.

For books like this one, authors are usually asked to put together an outline to help the publisher assess whether the book is, in fact, for them. It’s also a great way for authors to help think through and structure their thoughts. After O’Reilly contacted me about writing this book, I outlined the book as requested. Some authors find outlines to be incredibly helpful, and others find it limiting or even a blocker for their writing process.

When you search for advice on how to go about writing, for example, a novel, the advice is often to just sit down and write. A writing blog called The Write Practice recommends you write your first draft in as short a time as possible:―a sitting if it’s a short story, or a season (three months) if it’s a novel.5 While writing this first draft, the consultants don’t recommend worrying too much about plotting or outlining. That can come once you know you have a story to tell. The purpose of that first draft is very much a discovery process, in which you figure out what you actually have. Many writers will write three or more drafts:

The first draft

This is often a rough draft, sometimes called the “vomit draft.” It’s not to be shared with anyone. It’s your own draft, and it’s there to help you figure out what it is that you’re writing.

The second draft

Though this tends to be more refined, it is not for polishing. In the second draft, you carry out major structural changes and you clarify the plot and the characters, or the idea for your nonfiction book.

The third draft

This is the one for deep polishing and where, according to The Write Practice, the fun begins.

While this certainly holds true for how this book has come about, others would disagree with this approach. There is also some debate around whether writers should worry about identifying their theme: some say not until after writing a first draft, and others say the theme is such an integral part that it should be present throughout the story development. One can argue that it doesn’t matter how you go about writing your book or whether you lead with characters, or a theme, or whether you have a clear structure—as long as you write and a page-turning story comes out at the end.

Developing Your Content and Product Experience Story

For product design, the equivalent of how to go about writing your story is how to go about defining what that product should actually be and the content and features it should contain. Chapter 6 noted that some projects are led by the big idea rather than the needs of the characters. In film, the equivalent is a particular scene or use of the latest special effects that drives the story in a particular direction. How you come up with your story or your product idea doesn’t really matter, as long as it resonates with its intended audience.

Unfortunately, this is often where many products fall flat because what’s being designed and developed is not based on the priority of actual user needs. Or, although the idea is good, the project lacks a clear information architecture and content strategy to make it happen and give users the type of content that they need in a way that makes sense to them.

The number of projects in which an amazing-looking website or app has been created in Photoshop, Illustrator, or Sketch only to be developed and then look nothing like it is far too many. And it’s not due to poor development. Most of the time, it’s due to a lack of content planning, creation, and governance combined with a lack of collaboration between the design team and those responsible for creating or adding in the content. It doesn’t matter how great the website or app looks in design, or how good the idea is, or how well it meets the research findings if what actually goes into the website or app in terms of content doesn’t match the basis on which it has been designed.

Just as an outline and defined theme will help some authors plan out their books, and help publishers assess the relevance and value that such books can provide, there are a number of tools and methods that product teams should work with to help plan out and assess the value of a website or app. Three of these are sitemaps, card sorts, and content plans.

In addition to these, in this book we’ve covered methods from traditional storytelling (such as the index card method in Chapter 5), which helps you plan out the overall narrative and start to identify the different parts of the experience from sequences, scenes, and plots. We covered experience goals in Chapter 9, which help define the theme of the product experience, and we talked about main plots and subplots in the previous chapter. All of these, combined with the tools and methods we are used to using, such as sitemaps, help provide reference points and a framework for ensuring that our product experience has a theme running through it all, working as a guiding northern star for the product experience’s story development.

What Storytelling Teaches Us About Theme and Developing Your Product Story

To tell a great story, you need to know what you’re saying and to consider who you’re telling it to. Chapter 5 described the plot as what you’re going to tell your audience when; defining the plot of your product experience will help form a better understanding of the full end-to-end experience. Just sitting down and writing rather than preparing a full outline may have some advantages in traditional storytelling. But for product design, we risk becoming too focused on the detail, such as specific screens, before having a solid understanding of the bigger picture. By working through the narrative structure in one of the ways covered in Chapter 5, you’ll have a solid foundation for going into both content strategy and information architecture. While in UX design it is about delivering the right content at the right time, on the right device, it’s also about having the right content in the first place. As Joseph Phillips writes for GatherContent, “A huge part of content strategy actually has nothing to do with content itself. It’s about people.”6

Identify Your Theme

Journalist Larry Brooks argues that there is an important distinction between concept, idea, premise, and theme. These terms are often used interchangeably, he says, but in the wrong way, as they are different. Using The Lovely Bones by Alice Sebold (Oberon Books) as an example, he explains the differences as follows:

The idea

To tell a story about what heaven is like

The concept

To have a narrator who is already in heaven narrating the story and then turn it into a murder mystery. Or, if put as a question: “What if a murder victim can’t rest in heaven because her crime remains unsolved, and chooses to get involved to help her loved ones gain closure?”

The premise

“What if a 14-year-old girl cannot rest in heaven, and realizes that her family cannot rest on earth, because her murder remains unsolved, so she intervenes to help uncover the truth and bring peace to those who loved her, thus allowing her to move on?”

The theme

What does the story mean?

Brooks conveys that an idea is always a subset of a concept, and a concept, in turn, is a subset of a premise. What makes something a concept is the qualifier. This qualifier can be expressed using a “What if…?” proposition. By simply adding this, you open the door to a story. You then have a premise when you throw a character into the mix and you, so to speak, expand the concept. In The Lovely Bones example, this is done by adding the hero’s quest into the “What if…?” proposition. The theme, on the other hand, is completely different and raises the question of what the story means to you; what does it make you think about and feel? It’s about the relevance of your story to life.7

How to go about it

In a nonliterary sense, a concept can still be called an idea, according to Brooks, and that fits well with how we’re at times using the terms idea and concept interchangably in product design. An idea can also come from the realm of a theme, just as an idea for a product can come from a theme such as financial planning. Just as writers may not always be clear about what their theme is, in product design, it can be the same thing. The Writing Forward blog gives the following tips on developing theme:

Learn to identify themes

Identify themes when watching movies and reading novels, as this will help you become better at bringing themes into your own work.

Don’t stress

A theme will usually emerge by itself as you work through your first draft.

Strengthen the theme

After you’ve identified the theme, make a list of related themes that you could weave into subplots.

Check your work

Make a list of all the themes in your story.

Whether you start by having a clearly defined theme or developing it as you start to explore and define the product or service doesn’t matter too much. The important thing is that you have a theme.

Explore Mental Models

One of our jobs as product and UX designers is to ensure that the right content appears in an appropriate order and is suitably structured and labeled so that finding our way around it is easy and makes sense. This should be based not only on needs, but also on mental models. Without thinking about it, we, and our users, organize information and items every day in our lives. Certain groupings just feel right or make sense, and others are ones that we’ve gotten used to. Making sure we meet these expectations is a critical part of structuring and organizing the content that we’ve defined. One of the best-known tools for organizing information is card sorting, a method used to help define or evaluate the information architecture of a website, app, or platform.

But it’s not just about making sure that the labeling and organization of information and content makes sense. When we work through and define our content and our information architecture, we should evaluate whether the structure that we’ve defined tells the story that the user is expecting. The tools we covered earlier in this book, (particularly Chapters 5 and 10) provide us with a good starting point for the different steps and the order in which a user would typically go about an experience. However, as we covered in Chapter 3, a user’s journey is seldom linear nowadays, nor does it necessarily start from the beginning that we’ve so carefully crafted. This means that we need to think about the overarching narrative across pages and views, and the narrative within each of those pages and views, as well as how they fit into the overall experience, no matter when or how a user ends up on them.

Summary

While all of us will have different preferences for the ways we work and come up with the ideas for our product, there is something to be said about having a process or strategy. Processes give us a structure to follow. As the start of any project is usually chaotic (whether it’s related to product design or writing a book, play, or screenplay), processes—however light they are in their form—can help ensure that we’re on the right path and stay on it.

Chapter 5 defined plot as what you’re going to tell your audience when. The role of theme and story development is about defining the red thread, or through line, that binds the parts of the plot, and the whole product experience, together, and then developing the content strategy and information architecture to go with it.

As we’ve covered in this chapter, in all good stories, things happen for a reason, and all the content of the product and services that we design should be there for a reason as well. To achieve that, we have to make sure that through everything we do and say, we’re clear on why and how to refer to that content so it best resonates with our users.

1 Robert McKee, Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting (New York: ReganBooks, 2006).

2 Larry Page, Story Engineering (Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2011); Courtney Carpenter, “Exploring Theme,” Writer’s Digest, April 30, 2012, https://oreil.ly/N7X8k.

3 Melissa Donovan, “What Is the Theme of a Story?” Writing Forward, October 15, 2019, https://oreil.ly/DYgc_.

4 Barri Evins, “The Power of Theme,” Writer’s Digest, August 17, 2018, https://oreil.ly/tDdHr.

5 Joe Bunting, “Ten Secrets To Write Better Stories,” The Write Practice (blog), https://oreil.ly/1U1s3.

6 Joseph Phillips, “A Four Step Road Map for Good Content Governance,” GatherContent (blog), October 1, 2015, https://oreil.ly/vIQcr.

7 Carpenter, “Exploring Theme;” Larry Brooks, “Concept Defined,” Writer’s Digest, November 22, 2010, https://oreil.ly/ENHEp.